LIGHTING THE PANAMA-PACIFIC INTERNATIONAL EXPOSITION

By John Winthrop Hammond

"I have tonight seen the greatest revelation of beauty that was ever seen on the earth," exclaimed Edwin Markham, the poet, one February evening in 1915.

"I may say this, meaning it literally," he added, "and with full regard for all that is known of ancient art and architecture, and all that the modern world has heretofore seen of glory and grandeur. I have seen beauty that will give the world new standards of art and a joy in loveliness never before reached. This is what I have seen–the courts and buildings of the Panama-Pacific Exposition illuminated at night." The illumination which so inspired the poet was largely the work of Walter D'Arcy Ryan, director of General Electric's Illuminating Engineering Laboratory.

Ryan had tackled illuminating jobs of this magnitude before. In 1907 he had supervised the lighting of Niagara Falls–a feat that required the installation of batteries of projectors giving a combined illumination equivalent to 1,115,000,000 candles. It, too, had been a huge success. The throng that gathered on the opening night was so large that the suspension bridge swayed perceptibly and traffic had to be halted. The roar of the cataract came through the darkness, the cataract that could not be seen. Then without warning the Falls leaped out of the night, a vast, shimmering mist of plunging water, gleaming in the concentrated light, The thousands of spectators stood in awe and silence.

Ryan had tackled illuminating jobs of this magnitude before. In 1907 he had supervised the lighting of Niagara Falls–a feat that required the installation of batteries of projectors giving a combined illumination equivalent to 1,115,000,000 candles. It, too, had been a huge success. The throng that gathered on the opening night was so large that the suspension bridge swayed perceptibly and traffic had to be halted. The roar of the cataract came through the darkness, the cataract that could not be seen. Then without warning the Falls leaped out of the night, a vast, shimmering mist of plunging water, gleaming in the concentrated light, The thousands of spectators stood in awe and silence.

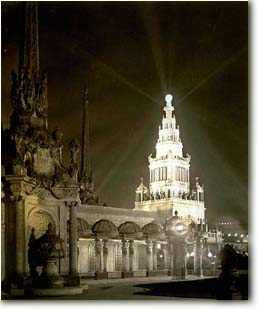

But Ryan encountered new difficulties when, in San Francisco, he presented his plans before the architects, designers, and color artists who were involved in preparation for the Exposition. His proposals seemed so fantastic that there was scarcely a detail which was not opposed. For Ryan's theory was founded upon the idea that to run strings of incandescent lamps along the edges of buildings so that they would be outlined by dots of light, was crude and archaic. His plan was twofold: first he proposed to throw a flood of light upon the facades of the buildings; and second, he proposed a scheme for depth, or "shadow" lighting. A terraced tower, four hundred feet or more from a square base with broad archways, dominated the wide array of picturesque Spanish mission buildings. Ryan's idea for lighting this tower was even more fantastic. He wanted something lively and prismatic. Immediately he thought of imitation cut-glass jewels played upon by powerful searchlights. He instituted a search which finally uncovered a type of jewel made in imitation of diamonds, rubies, sapphires, and emeralds and the glass was so cut as to possess a high index of refraction.

Many cunning hands had worked over those gems. Native workmen among the hills of Austria had kept the craft in their families for generations, treating the original uncut pieces by heat and glass-blowing methods of which they alone knew the secret. In 1913 there came from distant America an order for no less than 130,000 jewels!

Many cunning hands had worked over those gems. Native workmen among the hills of Austria had kept the craft in their families for generations, treating the original uncut pieces by heat and glass-blowing methods of which they alone knew the secret. In 1913 there came from distant America an order for no less than 130,000 jewels!

The Austrian craftsmen gasped, but in time the order was filled. Ryan called the jewels "Novagems." His laboratory workshop, crowded with color paintings of the buildings as they would appear when illuminated, color charts, and booths for demonstrating special illumination effects aroused the greatest curiosity. Some of the other specialists felt that Ryan was usurping the functions belonging to others. Upon returning from one of his trips East, Ryan found that his critics had burst into open condemnation of his plans. Someone had tried a few of his jewels upon the tower and found that they cast shadows. The architects' commission wanted to throw all the jewels bodily into San Francisco Bay.

Ryan promptly demonstrated by means of photographs that, when properly mounted, the jewels would not cast shadows, while incandescent lamps, strung up and down the tower would. Then he was told that his idea of placing heraldic banners along the avenues to add color in the daytime and to screen floodlight units at night would cheapen the exposition into a mere Coney Island spectacle because the banners would flap. Ryan replied that he intended to hang fifty-pound weighted tassels from each banner so that no ordinary breeze would disturb them.

Another outcry went up when he disclosed his plan for a steam scintillator to be played upon by a great battery of electric searchlights. He had arranged with the Southern Pacific Railroad to have a steam locomotive, painted a rich cream color, backed upon a pier on the waterside front of the exposition. Shell pits were dug and forty-eight big searchlights were placed in position, their total capacity equaling 2,600,000,000 candles. Surely "this man Ryan" was running wild! The architects' commission started a movement to have the locomotive removed.

Another outcry went up when he disclosed his plan for a steam scintillator to be played upon by a great battery of electric searchlights. He had arranged with the Southern Pacific Railroad to have a steam locomotive, painted a rich cream color, backed upon a pier on the waterside front of the exposition. Shell pits were dug and forty-eight big searchlights were placed in position, their total capacity equaling 2,600,000,000 candles. Surely "this man Ryan" was running wild! The architects' commission started a movement to have the locomotive removed.

But Ryan would not be stampeded. He stoutly defended his "fireless fireworks." The locomotive and the steam scintillator remained.

But exposition officials were secretly as fearful as the architects and designers. They hoped that Ryan was right, while they quietly consulted a local illuminating expert and had an alternate plan worked out down to the last detail, ready to be rushed into the gap should the Ryan plan fail upon trial. This alternate plan was based upon strings of incandescent lamps.

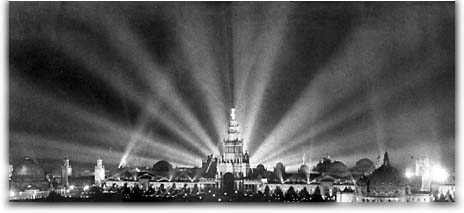

At last came the night for the trial exhibition, the night of February 15, 1915, three weeks before the date of the official opening. Upon one of the wide avenues the official party gathered. Dusk slowly began to fall. A silvery shaft leaped into the darkening sky.

Then, in a burst of glory, a scene of romantic beauty unfolded, as palaces and halls stood out richly down long thoroughfares of light. Radiance glowed from every window, as if the interiors were brightly lighted. Deep rose tints bathed the recesses in archways and columned porticoes, where forbidding shadows usually gathered. It was a city of light.

In the center rose the iridescent Tower of Jewels. And every pool and lagoon caught and reflected the glimmering tower and the fairy palaces. A 20th Century Aladdin had rubbed his lamp.

The international jury of awards of the Exposition did something never before dreamed of. It adjudged the illumination of the Exposition to be a "decorative art."

Hammond, John Winthrop, 1887-1934.

Men and Volts; the story of General Electric, by John Winthrop Hammond.

Philadelphia, New York [etc.] J. B. Lippincott Company [c1941].

See San Francisco History Index for more on the Panama-Pacific International Exposition.

Return to top of page.

|